I started playing the cello aged six, I trained classically, played in local youth orchestras and listened to recordings in awe of my heroine Jaqueline Du Pre. Then aged eleven (thanks to a childhood spent also listening to my Dad’s record collection), I had a new crush. This time John Bonham became my headphone mainstay.

I lived a marvellous double life as a teenager floating between the notes of Bach and Elgar and the paradiddles of Buddy Rich and splashes of Stuart Copeland. But I didn’t know there was a world in which I could use my newly acquired musical skills to earn a living.

MU support helped me develop my career

My first paid job came to me accidentally. I was actually working in the kitchen of a residential recording studio, washing dishes, when I overheard a producer saying the cellist hadn’t turned up. During the subsequent couple of hours I convinced him (and my boss, the kitchen chef) to let me go home, get my cello and return to play.

Turns out I did a better job than they expected, and that one lucky break gave me my entrance into a world of session work I hadn’t even dared to dream existed when I left school.

The MU played a fundamental part in helping me continue to do this. I plotted my years out in the pocket diary I received once a year and insured my equipment and instruments. I also used the free legal and medical services when I needed both starting out.

I don’t know if without this early support I would have been able to develop my career the way I did.

Songwriting to scriptwriting

As a songwriter and recording artist I have released a few albums, but it was during Covid and the stalling of my latest project - started with legendary producer Mike Hedges (The Cure, Travis) - that my career took another unlikely swerve.

I played some of the demos from the project to a couple of friends who suggested the music was very cinematic and that instead of just sitting on them, I should try to get them put in a film or tv show. So I wrote to the only production company I knew, EMU films to see if they’d like to do exactly that.

They wrote back saying how much they enjoyed the tracks and that in their opinion, a film should be written around the songs.

Various discussions were had with numerous, very talented, directors and writers including Carl Hunter (film director and sometimes bassist for The Farm) and Frank Cottrell-Boyce (writer of Millions). But in the end everyone was so busy (due to being so wonderfully brilliant at what they do), that I knew it could take years for the project to get off the ground and a feature film did feel a bit ambitious.

So one day, I’m still not sure exactly what came over me, I decided I’d give script writing a go myself. A short film seemed to be a more realistic goal and before I knew it, I was knee deep in draft ideas writing about the only thing I really felt confident to write about accurately, myself.

Turning memories into a screenplay

Around the same time that I started playing cello, my father was diagnosed with a very aggressive, deadly cancer. Days were peppered with moments of freedom and joy, learning my way around this strange classical instrument and its new language, as well as anxiety and fear watching my Dad shrink in size, grow paler and balder.

I started to invent alternative worlds in shoe boxes where everything was happy and normal, humming melodies I wrote myself on the back of the manuscript the teacher’s notes were on.

Turning these memories into a screenplay about hope and the power of our imagination to get us through even the most awful of times was less tricky than I thought.

However I did have an embarrassing moment when I sent my finished Word document to a friend who works in advertising for critique - they had to gently tell me that screenplays need to be formatted “in a certain way”. So I learnt how to do that (sort of) and sent the script to EMU, who to my astonishment agreed to produce the film with me.

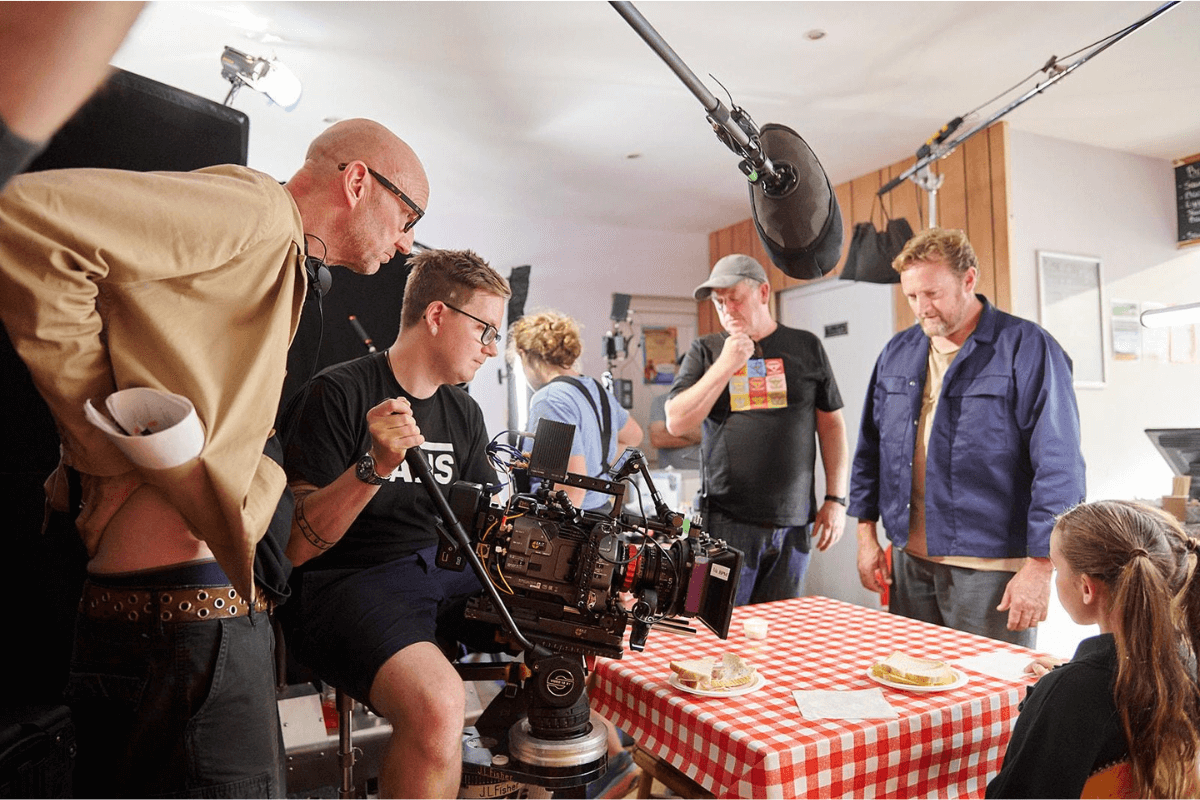

They found me a director and the script went through a couple of more practical changes as we worked together. Filming itself was a totally new experience, but it was fascinating and great to be so involved as it allowed me to really place the music almost within the script. For example, our lead actress hums a theme near the beginning that is then reprised as the main orchestral arrangement at the end of the film.

Composing music for film

Composing the music was also a huge learning curve, as it was the first time I’d purposely written for film. The initial idea to just place the music I’d already written in the film was quickly forgotten as I understood how I wanted the music to affect and support the visuals.

Instead I used the original songs as a template, from which I recomposed to create the main “themes” for the soundtrack with my colleague and fellow composer Pete Davis (PJ Harvey, Dido).

Together we worked on how to sonically support the two visual worlds in the film, that of the imaginary shoe box (which we shot live in a studio in Manchester, manipulating cardboard characters made by set designer Paul Kondras) and the real life footage, shot over four days in Morecambe Bay.

We played about with recording in mono for the first half of the film and stereo for the second to emphasise the changes in mood which I think works really well. We also mixed in Atmos (Dolby sound technology), which was its own learning curve. Wider Than the Sky was born.

The world of short film festivals

Once we’d finished the film I thought the journey was pretty much over, but thanks to advice from EMU and a lucky break getting on film festival agent Festival Formula’s books, we entered the world of festivals for short films.

It was a bumpy start the first few months. Tumbleweed entered my email account and to be honest, I wasn’t that surprised. Being my first film and compositional endeavour on this scale, I wasn’t expecting too much. But suddenly around July last year we started getting selections.

Now, three quarters of the way through our submissions, we’ve had 28 selections around the world and the film has won eight awards, including the Performance Aviva Best Short Drama Award and Best Actress for our young lead, Willow Bell, at BIFA qualifying Birmingham Film Festival.

Advice for others when composing their first soundtrack

I’d definitely say to anyone thinking about composing their first soundtrack, get plenty of technical advice from someone who’s done it before.

It helped me enormously to work with my production and programming colleague Pete Davis. Because he’d composed for film in the past, he was able to organise how we worked and also give invaluable insights into how to develop themes.

It was also great working as a team when we encountered larger technical problems. For example, I was sure it would be a good idea to mix in Dolby Atmos but in hindsight, it didn’t add as much as I thought it would to the final overall experience. Especially considering how many problems we had making it happen, but having a team mate made the difficult parts of the journey much more bearable.

Looking forward

I’m not sure what is next after our festival run. I understand it’s hard for short films to have much of a life after this, but I’d love to see if there’s some cancer charities we could work with, maybe screening the film in schools.

As a result of now having attended so many festivals, I’ve identified a real lack of recognition for composers within the short film awards world. This is something that, in conjunction with the London Short Film Festival, I am hoping we can rectify by starting a prize for composers.

And of course there’s the soundtrack itself. Released on my own label Pop Fiction Records, it’s available to stream on all the usual platforms, including Apple and Spotify.

Learn more about ‘Wider Than The Sky’ and listen to the soundtrack.