This year the Musicians’ Union marked its 130th anniversary. It’s a momentous achievement, not least because expectations for a union that represented working musicians were so low when the Union was formed back in 1893. A previous attempt had failed just two months earlier and musicians were first in the firing line when the profits of the exploitative theatre owners who hired them dropped.

But that was the year when the working classes rose up in a solid demonstration of unity that would lead at the end of 1893, to a long and bitter miners’ strike. The balance of industrial relations was shifting and for early 1890s musicians, viewed as expendable by employers, the time was right to unite.

Over the following 130 years, the Musicians’ Union has tackled a relentless series of challenges, from the onset of talkies and the rise of gramophone records to racism, sexual discrimination, exploitation and an ever-shifting technological landscape.

Throughout it all, the MU has remained steadfast in its ongoing commitment to protect, support, and empower its members.

Protecting working musicians since 1893

It was April 1893, when clarinettist Joseph Bevir Williams sent an open letter to other musicians in Manchester inviting them to a meeting to discuss the formation of a union. The aim of this new union, wrote Williams, would be to “Protect us from amateurs, protect us from unscrupulous employers and protect us from ourselves”.

Williams was only 20 years old, but he was a formidable character. He was a member of the orchestra at Manchester’s Comedy Theatre, had been teaching clarinet and playing in orchestras since he was 16 years old, and knew only too well when musicians were being exploited. The pay for musicians in the early 1890s was paltry, working conditions were poor and they were expected to attend additional rehearsals for no extra pay.

The Amalgamated Musicians' Union makes its mark

The union that Williams formed was called the Amalgamated Musicians’ Union. The initial meeting attracted only 20 or so musicians, but within six months it had over 1,000 members. Assisted by his mother Kate, Williams enlisted the support of discontented musicians in Birmingham, Dundee, Glasgow, Liverpool, and Newcastle. The AMU grew fast and by the close of 1894, it had 17 branches and 2,000 members.

Manchester,1893, the year the AMU was formed. Image credit: © Musicians’ Union.

Manchester,1893, the year the AMU was formed. Image credit: © Musicians’ Union.

The AMU faced its first serious test the following year in 1894, when the orchestra - including Joe himself - refused to agree to a five shilling pay cut at Carl Rosa’s Royal Court Theatre in Liverpool. Joseph Williams led a strike and the majority of the orchestra’s wages were reinstated.

In 1904, Williams attended a congress in Paris, which led to the formation of the International Confederation of Musicians. By then, the AMU’s presence was really becoming evident. In 1909, police boats intervened when the AMU organised a floating protest over the use of military band musicians alongside the Houses of Parliament on the Thames.

The impact of cinema or ‘talkies’ on musicians

In 1921, after long-running disputes, the AMU merged with the National Orchestral Association, and the AMU officially became the Musicians’ Union. One year later, Joe Williams became chairman of the TUC General Council.

Large numbers of musicians had lost their lives on the front lines during the First World War. Those who did return feared for their livelihoods. But the end of the war had sparked a boom for musicians, with the formation of the BBC and the employment opportunities it brought.

But in 1928, a major calamity emerged: the advent of the ‘talkies.’ “The closure of so many orchestras when talking pictures arrived is one of the biggest crises the Union has had,” recalled former MU General Secretary John Smith in 2013. “Big cinemas would have a hundred or so musicians on full-time contract who’d be waiting for the latest scores to come off the ocean liners from the USA. Yet when one door closes another one opens — soon after the introduction of the talkies the BBC became a big employer.”

The threat to live music from technology

Before long, another threat came into view: the introduction of the gramophone into British households. Live music was now under attack from technology and it was a theme that would continue, in one guise or another, up to the present day. It would also produce some of the MU’s most creative responses over the coming decades, such as the Keep Music Live campaign, launched in the 1960s, promoted by its iconic sticker.

Not all the MU’s responses were so effective. When Duke Ellington appeared in the UK in 1933, the MU’s failure to strike a reciprocal deal with its US counterpart the American Federation of Musicians, prevented any visit from US dance bands to the UK for the next 15 years.

In 1943, the MU formally affiliated itself to the Labour Party and in 1948, Kay Holmes became the first woman elected to the Union’s Executive Committee. Two years later, following an insightful motion to the Union’s 1949 Delegate Conference, the first issue of the MU’s magazine The Musician was published.

The Union combats racism

In many ways, the Union’s biggest challenges over the years have been protecting its members in the face of profound technological and political change.

The Second World War had brought racism to the fore and this was an issue that exploded fiercely in the post-war era. The Musicians’ Union had taken a strong stand against the rise of fascism in the 1930s and it reacted quickly in the post-war era to register its opposition to apartheid in South Africa.

In 1957, the MU banned its members from performing in South Africa to segregated audiences. In the UK, meanwhile, some club proprietors exploited the culture of fear to invoke colour bars. In 1958, the MU withdrew the services of its members when such a colour bar was introduced at the Wolverhampton Scala.

Shifting musical styles: the impact on members

Cultural shifts have certainly had an impact. From jazz, skiffle, rock ‘n’ roll and 60s beat groups to DJs, hip-hop, drum ‘n’ bass and beyond, musicians’ livelihoods had been impacted by shifting styles across the decades. “The chill wind from the North” was how Humphrey Littleton described The Beatles and those who followed in their wake, whose appeal limited the gigging options for Lyttleton and his jazz contemporaries.

Each new genre has sounded alarm bells in some quarter or other. The skiffle boom in late-50s Britain prompted demands that skiffle musicians be excluded from the Union on the grounds that they weren’t real musicians. It was a view echoed when some questioned whether those playing Hammond organ should be entitled to Union membership.

The emergence of the synthesiser in the late-70s was similarly contentious and when Barry Manilow toured the UK in 1982 with a bank of synthesisers replacing his orchestra, the London branch called for an outright ban on synths. But synth players were subsequently welcomed into the Union, just as DJs would be in 1997, despite issues about remixing and sampling.

The MU calls strike over BBC cuts in 1980

In 1980, the MU faced one of its greatest challenges when the BBC decided to resolve its financial crisis by slashing five of its 11 in-house orchestras at a cost of 153 full-time and 19 part-time jobs.

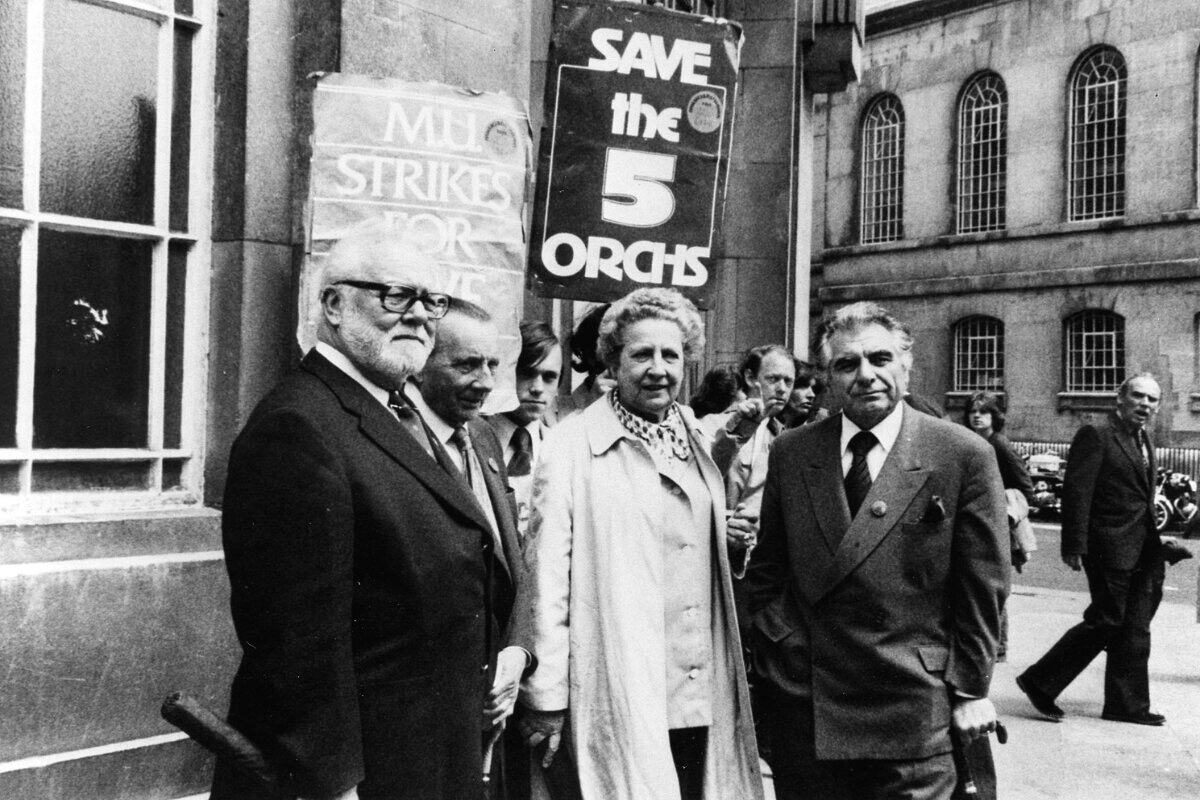

Charles Groves, Sir Lennox Berkley, Lady Barbirolli and Sir Geraint Evans join the picket line outside the BBC during the 1980 dispute. Image credit: © Musicians’ Union.

Charles Groves, Sir Lennox Berkley, Lady Barbirolli and Sir Geraint Evans join the picket line outside the BBC during the 1980 dispute. Image credit: © Musicians’ Union.

The Union voted to strike, with an 83.6% majority, and on 1 June 1980, the music stopped. When the First Night of the Proms was cancelled, the lawyer and political adviser Lord Goodman chaired a meeting between the Arts Council, the BBC, and the MU. An agreement was hammered out, saving three of the threatened orchestras.

But the 1980s was not a healthy period for the MU. A drop in membership forced the MU to withdraw from the TUC as it was unable to pay the fees. With Thatcher and her anti-union Conservative government in power, the Musicians’ Union spent much of the 1980s fighting against restrictions to its activities, which diminished its ability to take industrial action.

In 1990, Dennis Scard replaced John Morton as MU General Secretary, while Barbara White became the second woman to be elected to the Executive Committee. In 1993, on the MU’s 100th birthday, Scard noted that “campaigns fought 100 years ago are still relevant today”.

The MU in the new millennium

In 2002, John Smith became General Secretary and following a strategic review in the Union’s structure, subscriptions and staffing, significant changes were introduced. Not least of which was the move from a 72-branch network to the six regions which remain in place today.

The changes brought renewed energy to the Union and in 2012, after substantial MU lobbying, the Live Music Act 2012 was passed. The Act allowed venues with a capacity below 200 to host live music between 8am and 11pm without the need to apply for a licence. It was a landmark moment and provided a significant boost to the grassroots live music sector.

In the last ten years, the MU’s challenges have been immense. The Brexit referendum of 2016 sounded the death knell for many artists who relied on revenue from touring in Europe. The paltry revenues from streaming only heightened the fact that without live income, many musicians would be unable to make a living. Then in March 2020, the global pandemic ended live music in its tracks and left thousands of musicians facing severe hardship.

The Union, led by its General Secretary Horace Trubridge, moved swiftly to offer financial support to members and lobby for greater government assistance. The Union’s response during the pandemic is arguably one of its finest moments.

In March 2022, the MU elected its first female General Secretary, Naomi Pohl, and the Union, formed by the young Joe Williams back in 1893, is now in very good health. Membership is steadily rising, and at the time of writing has reached 33,300 members.

On this momentous anniversary, the MU can reflect on battles won and lost over the last 130 years and look to the future, protecting, supporting, and empowering its members for the opportunities and challenges that lie ahead.