The world of the Music Copyist is a mystery to most people and often, I think, even to the rest of our colleagues in the music business. So, who and what is this mythical creature, the Music Copyist?

Back in Mozart’s day it is documented that he used to fling finished pages of scribbled score out of the window to the waiting copyist, who would scurry away with them and literally copy them into individual parts for every musician – no printers or photocopiers then!

And until the computer became a standard piece of kit, we the late 20th century music copyists, fulfilled a similar function.

Copyists have often spent the nighttime hours sitting bleary eyed around some unfortunate arranger or orchestrator’s dining room table as they churned out pages of handwritten score, with us following on producing handwritten parts - the ink wet on the page was often a true statement. This would be followed by a frantic rush to the studio for a morning session.

The term Music Preparation really describes our activities better

However, the title Music Copyist is a misnomer nowadays since there is very little actual ‘copying’ involved. With the advent of various music notation programmes and all the printing and processing that we do, the term Music Preparation really describes our activities better.

We are the link between composer, orchestrator and performing musician.

Without the involvement of an efficient and experienced music copying team on a project, parts presented to the musicians (even with the modern day benefit of music notation programmes, which tend to be less than optimum), might be: too small on the page; not spaced correctly; feature rests notated wrongly; have no bar numbers or page turns; have parts missing or parts not transposed. It might also be taped badly on thin curling paper - poor musicians! We feel so sorry for them when this is the case.

These factors are all critical to help the success of a session or performance, and to give the musicians every possible chance of giving their best under the immense pressure of the red light and audience which they face every day. Beautiful sets of parts and scores are our goal, and this is the reason you need to use experienced music copyists on your project.

Immaculate material appearing on the music stand however is only the final part of a much more involved process, especially for a large-scale project like a film. So how do you estimate the cost of such a project?

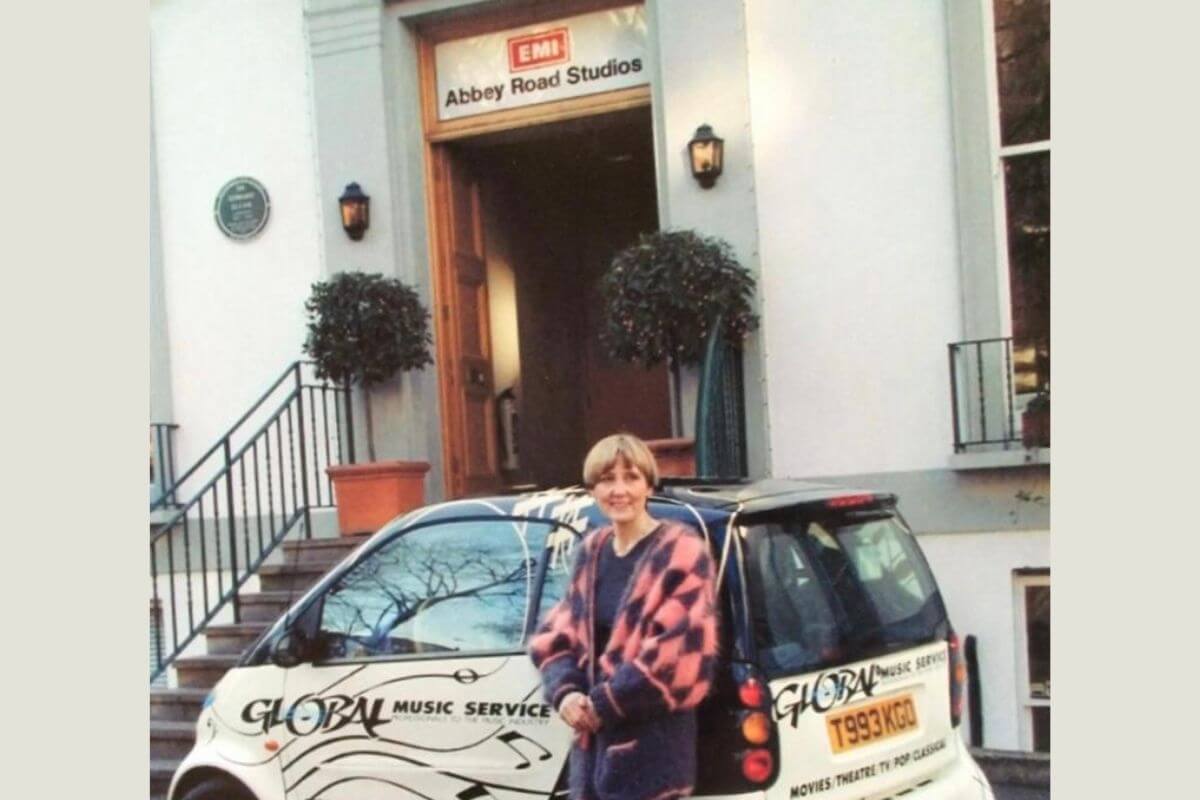

Jill has been making a living from music preparation for the last 40 years. Image credit: Jill Streater.

Jill has been making a living from music preparation for the last 40 years. Image credit: Jill Streater.

Estimating project costs

The starting point nowadays will usually be an email from somebody involved in the project – very rarely the composer or orchestrator. Frequently the wording goes something like this:

“We have a project coming up - hoping to record [dates]. There will be [number] musicians and it’ll be around [number] minutes of music. Are you available and please can you give us a quote as to how much it will cost?”

Immediately there are a number of questions. There is no way it is possible to come up with a figure based on the initial information. So, I buy a bit of time by asking lots of questions back. The sort of questions I need answering are:

- What is the actual lineup? It’s particularly important to know how many string desks, percussion or choir there are, all of which will involve extra work.

- What genre of project is it? For example, a superhero movie will usually involve a lot more work and printing than a small tv series, and an animation will nearly always have very detailed and intricate woodwind parts which take time to separate out.

- Will there be overdub passes? A lot of composers use this device nowadays and on a large string section, it will add considerably to the bill (for example, when all players had to have separate folders of parts during Covid, that added a lot to the bill too).

- How many people are likely to be in attendance at the sessions? Pre Covid, I have had some sessions where there have been more than 10 sets of scores needed, but Zoom has definitely reduced this number. Given they are a lot of work to produce, it is important to get an idea of probable numbers of score sets needed before coming up with an estimate. It is also important to call it an estimate too, not a quote. There are many factors that can scupper even the best worked out figures.

- Do they have any idea of a cue list? Often they don’t, but even a rough list of the number of starts is definitely helpful.

- Do they need a librarian in attendance at their sessions? Sometimes we are very busy during sessions, sometimes we do nothing. The thing is, it is hard to predict, and it is definitely a worthwhile insurance policy to have someone there if the budget will allow for it.

We are the link between composer, orchestrator and performing musician. Image credit: Jill Streater.

We are the link between composer, orchestrator and performing musician. Image credit: Jill Streater.

Allowing for the unexpected

Armed with all these extra details, it’s time to put on the magic hat and conjure up some sort of range of figures for the client as an estimate.

I allow sensibly by working out the hours it might take, as well as an average number of pages per cue and multiplying this by the potential number of cues. Allow for the uexpected!

Allow for a supervisor charge if it is going to be a large team effort. Allow for extra materials such as custom-made folders, special tapes, ever more expensive paper, index tabs and getting printers to the studio.

I will then give two ranges of possible figures. Sensible-to-allow-worst-case-scenario (higher), and what I think it will very likely come in at (lower). Put it in an email, cross your fingers and send it off!

Join Jill and others in the Music Writers' Section

The MU Music Writers’ Section represents music composers, songwriters, arrangers and copyists. Section members can also get involved with the Section Committee work.

Find out more