They are some of the most prolific musicians in the world. They enjoy variety, benefits, travel and financial security unthinkable to most in the industry.

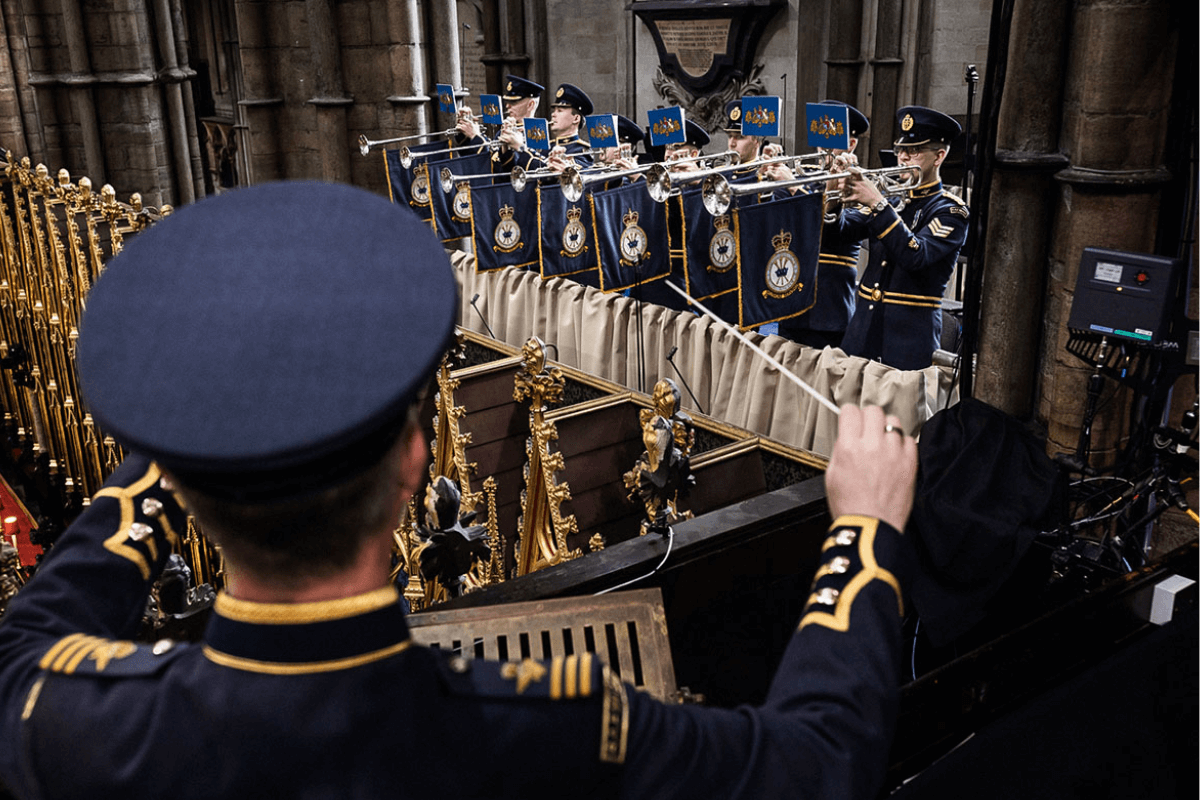

They number almost 1,000, surely making them the largest body of full-time players in the UK. And if you engage with British culture, you have almost certainly seen them in action, with the state funeral for Queen Elizabeth II and King Charles III’s coronation respectively drawing TV audiences of 29 and 18 million.

Yet the career of an Armed Forces musician is a path taken by relatively few of the MU’s 34,000 members. Perhaps, just as a combat career in the military evokes mental images gleaned from movies and TV, so the notion of joining the Armed Forces as a musician comes with preconceptions (often that it will involve a strict diet of marching music).

Speak to those with first-hand experience, however, and a different picture emerges, starting with the revelation that there is no such thing as a ‘typical’ background for the musicians who apply to the three main recruiting bodies, the Royal Corps of Army Music, Royal Air Force and Royal Marines.

There are various reasons musicians look to the military

“I was in a Championship Section brass band when I was 18 and saw a recruiting advertisement in the British Bandsman magazine,” reflects John Park, who served from 1985 to 2007 and was a Sergeant and Principal Percussion/Vocals in the Scots Guards band.

“In 1985, we’d just had the miners’ strike and there wasn’t a lot going on in the North-East, job and prospects-wise, so it seemed a logical move. I took the advert into the local Army Careers Office one Friday morning and on Monday, I was on a train to Bovington, Dorset for my audition. It was that fast!”

For Alan Thomas, becoming Principal Trumpet for the Central Band of the Royal Air Force was the realisation of a childhood dream. “The reason I played the trumpet was because I’d get taken to the Changing of the Guard by my parents,” he recalls.

“I intended to either join the Marines, Guards or RAF, but I went to music college and ended up playing classical. I did a postgrad at the Royal College, three years with the London Symphony Orchestra, then the City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra. But lockdown made me think: ‘Maybe I could revisit that military thing’. My first gig was the Duke Of Edinburgh’s funeral.”

For Julian Cook, meanwhile, it was a favourite teacher who lit the spark. “I played cornet and drums at school in Ipswich and was taught by a former Royal Marines musician who spoke to me about a career in the Royal Marines Band Service. I remembered watching them on TV at the FA Cup Final with their smart uniform, straight lines and distinctive white helmets and I thought, ‘That’s the job for me’.”

“The variety of work is something you wouldn’t get in a civilian band or orchestra. The RMBS are renowned for being versatile and perform in all types of ensembles.” Image credit: Crown Copyright 2023.

“The variety of work is something you wouldn’t get in a civilian band or orchestra. The RMBS are renowned for being versatile and perform in all types of ensembles.” Image credit: Crown Copyright 2023.

Entry requirements for an Armed Forces musician

Of course, as in any other branch of the military, application does not guarantee acceptance. It’s interesting to note the relative entry requirements across the three recruiting bodies, taking in everything from age limits to qualifications.

“The Royal Corps of Army Music is interested in your performance and potential,” says Park. “I had no formal musical qualifications at all. But I didn’t have to be the finished article, as you would in the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra. I had a few years’ experience of playing at a decent standard in the brass band world and was familiar with following a conductor. I’d had a good drum teacher and learned to read music, then got to practise it all twice a week at rehearsal, as well as concerts and contests.”

“If you can put all that together for an audition, have a positive outlook and think you can offer something, there’s no reason why you couldn’t become a Forces musician. I spent a year at the Royal Military School of Music at Kneller Hall, on a course with 150 musicians, having lessons from the legendary percussionist John Cave.”

Invited to the Royal Marines School of Music for his own three-day audition, Cook also encountered a character-focused selection process – and was thrown a curveball.

An individual doesn’t need grades, they just need to show musical aptitude and a can-do attitude, even when times get tough.

“For someone who is interested in a career in the RMBS, we look at a standard around grade 5,” he says. “However, an individual doesn’t need grades, they just need to show musical aptitude and a can-do attitude, even when times get tough. I passed the audition but I wasn’t offered cornet or percussion – instead, they offered me clarinet and violin, two completely new instruments!”

The RAF sets the highest bar for musical proficiency, but offsets this by welcoming seasoned players. “I thought I’d be too old,” admits Thomas. “But you can join the Royal Air Force until the age of 48. Musically, it’s a grade 8 standard. Most of our musicians, but not all, are university or music college graduates.”

Fitness is important for musicians in the military

Musical ability and strength of character might get you through the door, but some raw recruits don’t realise they will face the same training as incoming combat troops.

“They turn every civilian into a soldier,” says Park. “So it’s lots of PT, drill, crawling on your belly in mud. You obviously have to be trained to use a weapon, which in my case was a submachine gun. And you have to do a weapons test once a year.”

Musicians shouldn’t be intimidated by the physical demands.

Yet musicians shouldn’t be intimidated by the physical demands, reassures Thomas. “Everyone is daunted by the fitness test, but it’s not that bad, and if musicians are given a target, we’re very good at applying ourselves. Basic training is 10 weeks at RAF Halton. And fitness is important, even for the ceremonial things – you can’t be out of breath and march up the hill to Windsor Castle. And that continues, because you have a fitness test every year.”

Military bands perform a varied repertoire

For those whose knowledge of military music rests on a dimly remembered Royal Tournament, the repertoire might not seem much more than a scuttle of snare drum and brass fanfare.

Dig deeper, however, and you realise the remit of a Forces player rivals anything on civvy street, with the Army’s 14 internationally performing bands, for instance, performing genres including jazz, classical and pop in formats spanning from a full orchestra to a string quartet.

“It’s very varied,” says Thomas. “If you’re playing a serious symphonic wind band concert, you can play some quite heavy repertoire. But if the same band are playing a garden party at Buckingham Palace, it’s a different atmosphere, so the lighter side of the music comes out. Then there’s obviously the old Royal Air Force favourites as well – your Dambusters marches and things like that. I recently spent four weeks doing the Edinburgh Tattoo, performing in front of 8,000 people every night.”

The variety of work is something you wouldn’t get in a civilian band or orchestra.

“It’s not a normal 9-to-5 job and it can be long days rehearsing in the concert hall or on parade,” picks up Cook, “but the variety of work is something you wouldn’t get in a civilian band or orchestra. The RMBS are renowned for being versatile and perform in all types of ensembles.”

“This could be a small string, woodwind or brass ensemble for a regimental dinner, our world-famous Corps of Drums performing drum routines with stars like Take That and Queen, a function band or dance band performing at a wedding venue, a fanfare team playing the opening fanfare for an event, or a marching band performing in a foreign tattoo – all the way up to a full military wind band, performing in concert venues all over the world.”

As Park explains, the pool of musicians can be configured a thousand different ways depending on the event.

“There’s a full symphonic concert band and orchestra. But then there’s all the smaller groups shooting off that – brass quintets, string quartets, dance bands, pop groups, big bands. For the Festival of Remembrance, I’d warm up the crowd of veterans by leading a singalong of World War II songs. And if a celebrity vocalist isn’t available for the rehearsal, I would be there in their stead to rehearse the song. I depped for Will Young and Russell Watson.”

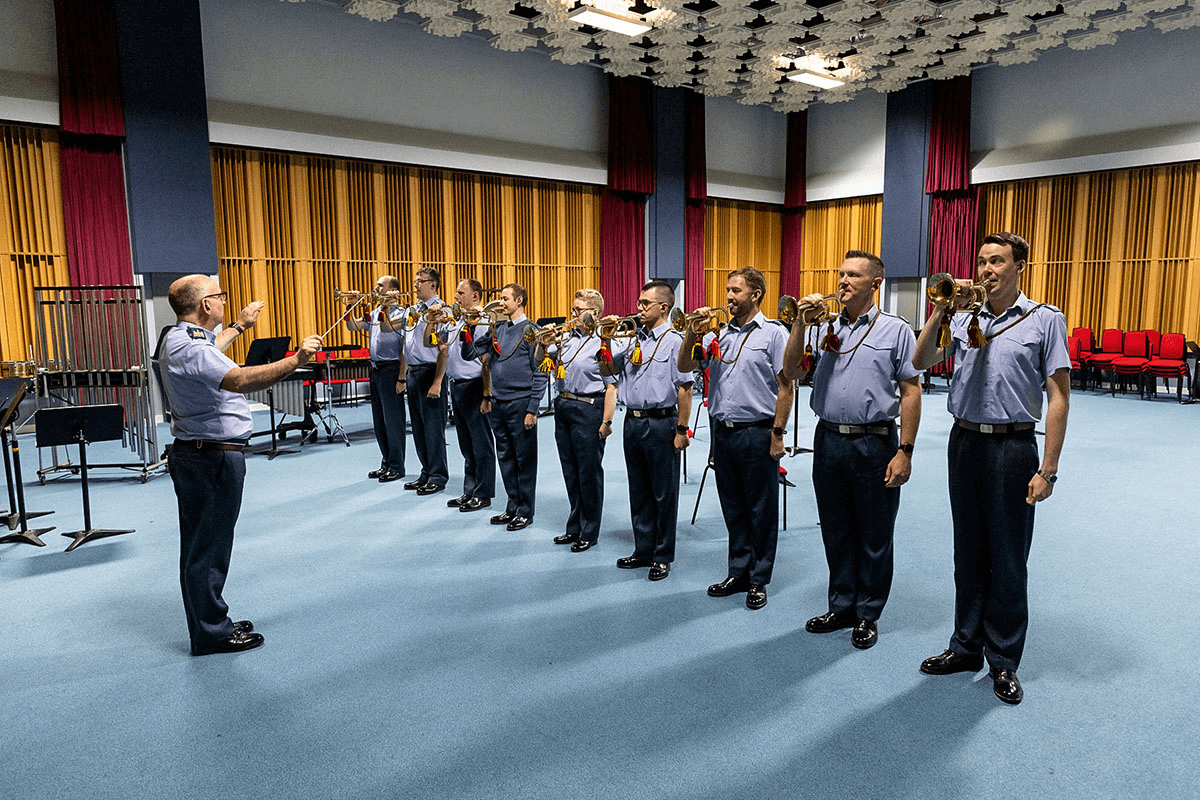

“We’ve got our own state-of-the-art band room with practice rooms and all the gear – they also kit you out with all the instruments you require ...”. Image credit: Crown Copyright 2023.

“We’ve got our own state-of-the-art band room with practice rooms and all the gear – they also kit you out with all the instruments you require ...”. Image credit: Crown Copyright 2023.

A chance to learn additional skills

The day-to-day existence of a Forces musician is not dissimilar from those in any professional orchestra, spent practising, perfecting and performing. Yet the basic military training given upon entry is no token gesture, says Park, with exceptional circumstances requiring musicians to lay down their instruments and call upon a secondary skill.

“When I was serving, I was a medic. I trained with the Medical Corps and refresher training was carried out once a year. I was deployed during the first Gulf War in 1991 and to Kosovo in 1999. That said, during my 22-year career as a Forces musician, this counted for around six months of it.”

For military musicians to step up in times of crisis is a grand tradition, explains Thomas. “Historically, they’d drive fire engines during a fire fighters’ strike. During my time, the band were used for COVID testing and even giving vaccines, and we’ve had members go out to check passports at Heathrow Airport.”

“Our current secondary role is in decontamination in chemical warfare. So we’re trained in that, just the same as we’re all trained how to use a rifle. So these things do happen, but it’s infrequent, because the band is busy in its role and we need at least 35 musicians to do a parade. Music is our day-to-day focus.”

The benefits of a musical military career

While the early starts and long days of a military musician hardly make this a soft option, there are undoubtedly benefits that will seem alien to those in the wider music industry. “We’ve got our own state-of-the-art band room with practice rooms and all the gear – they also kit you out with all the instruments you require, as well as mouthpieces, reeds, mutes, and so on,” says Thomas. “We even have our own green room. So the facilities we’ve got are brilliant.”

As long as you keep yourself fit, it’s a very secure job.

Factor in the job security and financial package, he adds, and the case for investigating this career path becomes more persuasive still. “As long as you keep yourself fit, it’s a very secure job. The starting salary in the band is over £31,000, and then you consider that we’ve got a non-contributory pension and subsidised housing. The other thing is, as a Forces musician, there’s career progression. Whereas, if you’re Principal Trumpet in an orchestra – where do you go?”

What’s next after a career in the Forces?

There is a level of commitment when joining the Forces – the Army, for example, requires you to serve a minimum of four years – but as John Park explains, it’s not uncommon for military musicians to take the skills they’ve learnt and apply them on civvy street. “I learnt so much and grew both as a musician and a person during my time in the Army. In 2007, I felt like it was time to move on – I had my feet under the table with a few different things, so I thought I’d be able to make it work.

“I went out of the frying pan into the fire when I left, because I was in a country-roots Americana band and we got picked by Take That to open for them on tour. I’m now on drums and backing vocals in a busy Madness and Specials tribute band – Special Kinda Madness. I sing for a big band, teach drums and percussion at two schools and I’m also the bandstand singer at Royal Ascot – I got that while I was still in the Army and I’ve been doing it for 16 years.”

Points to consider if you’re thinking about a career as an Armed Forces musician

- Have the right mindset - Perhaps more than any other sector of the music industry, a strong applicant for the Armed Forces will prioritise service, sacrifice and teamwork above individual glory, bringing a positive attitude to everything they do. “My advice would be to keep an open mind,” says Park.

- Study the entry requirements - Don’t set your heart on a Forces career until checking you meet the entry criteria. From minimum/maximum age to the required musical standard, do your homework and fix any holes you can in your résumé.

- Look out for bursaries - Financial help is available, with aspiring Army musicians currently studying for a music degree eligible for a bursary of up to £27,750 (£9,250 per academic year).

- Ask lots of questions - It’s easy to get in touch online and the recruitment team can fill in the blanks or even arrange no-commitment taster days. “There’s lots of information,” says Cook, “and we have careers advisors who can discuss the process with you.

- Don’t be intimidated - Joining the military is not a decision to make lightly, but neither should you expect the ferocious trial-by-fire often depicted in the movies/television. “It’s not as scary as everyone makes out,” says Thomas. “People don’t really shout at you!”